Bicycle

A bicycle, or bike, is a pedal-driven human-powered vehicle with two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other. First introduced in 19th-century Europe, bicycles evolved quickly into their familiar, current design. Numbering over a billion worldwide. Bicycles provide the principal means of transportation in many regions, are a popular form of recreation, and have been adapted for use in many other fields of human activity, including children's toys, adult fitness, military and local police applications, courier services, and cycle sports.

The basic shape and configuration of the bicycle's frame, wheels, pedals, saddle, and handlebars have hardly changed since the first chain-driven model was developed around 1885, although many important details have since been improved, especially since the advent of modern materials and computer-aided design. These have allowed for a proliferation of specialized designs for individuals who pursue a particular type of cycling.

The bicycle has affected history considerably, in both the cultural and industrial realms. In its early years, bicycle construction drew on pre-existing technologies; more recently, bicycle technology has, in turn, contributed ideas in both old and newer areas.

History

Main article History of the bicycle

Several inventors and innovators contributed to the development of the bicycle. Its earliest known forebears were called velocipedes, and included many types of human-powered vehicles. One of these, the scooter-like dandy horse of the French Comte de Sivrac, dating to 1790, was long cited as the earliest bicycle. Most bicycle historians now believe that these hobby-horses with no steering mechanism probably never existed, but were made up by Louis Baudry de Saunier, a 19th-century French bicycle historian.

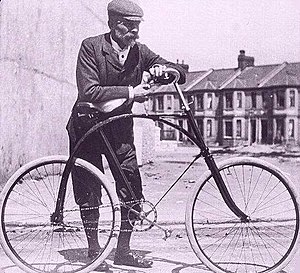

The ancestor of the bicycle was probably first created by a German Baron, Karl Drais, who invented and patented his machine in 1817. A number of these draisines still exist, including one at the Paleis het Loo museum in Apeldoorn, the Netherlands. These were pushbikes, powered by the action of the rider's feet pushing against the ground. Scottish blacksmith Kirkpatrick MacMillan refined this in 1839 by adding a mechanical crank drive to the rear wheel, thus creating the first true "bicycle" in the modern sense. His system employed a pair of treadle drives connected by rods to a rear wheel crank, rather like a steam locomotive's driveshaft. Although the design was copied by at least two other Scottish builders, it was overtaken in popularity and influence by an inferior one. In the 1850s and 1860s, Frenchmen Ernest Michaux and Pierre Lallement took bicycle design in a different direction, placing the pedals on an enlarged front wheel. Their creation, which came to be called the "Boneshaker", featured a heavy steel frame on which they mounted wooden wheels with iron tires. Lallement emigrated to America, where he recorded a patent on his bicycle in 1866 in New Haven, Connecticut. The Boneshaker was further refined by James Starley in the 1870s. He mounted the seat more squarely over the pedals so that the rider could push more firmly, and further enlarged the front wheel to increase the potential for speed. With tires of solid rubber, his machine became known as the ordinary. British cyclists likened the disparity in size of the two wheels to their coinage, nicknaming it the penny-farthing. The primitive bicycles of this generation were difficult to ride, and the high seat and poor weight distribution made for dangerous falls.

The subsequent dwarf ordinary addressed some of these faults by adding gearing, reducing the front wheel diameter, and setting the seat further back, with no loss of speed. Having to both pedal and steer via the front wheel remained a problem. Starley's nephew, J. K. Starley, J. H. Lawson, and Shergold solved this problem by introducing the chain and producing rear-wheel drive. These models were known as dwarf safeties, or safety bicycles, for their lower seat height and better weight distribution. Starley's 1885 Rover is usually described as the first recognizably modern bicycle. Soon, the seat tube was added, creating the double-triangle, diamond frame of the modern bike.

While the Starley design was much safer, the return to smaller wheels made for a bumpy ride. The next innovations increased comfort and ushered in the 1890s Golden Age of Bicycles. In 1888, Scotsman John Boyd Dunlop introduced the pneumatic tire, which soon became universal. Soon after, the rear freewheel was developed, enabling the rider to coast without the pedals spinning out of control. This refinement led to the 1898 invention of coaster brakes. Derailleur gears and hand-operated, cable-pull brakes were also developed during these years, but were only slowly adopted by casual riders. By the turn of the century, bicycling clubs flourished on both sides of the Atlantic, and touring and racing were soon extremely popular.

Successful early bicycle manufacturers included Englishman Frank Bowden and German builder Ignaz Schwinn. Bowden started the Raleigh company in Nottingham in the 1890s, and was soon producing some 30,000 bicycles a year. Schwinn emigrated to the United States, where he founded his similarly successful company in Chicago in 1895. Schwinn bicycles soon featured widened tires and spring-cushioned, padded seats, sacrificing a certain amount of efficiency for increased comfort. Facilitated by connections between European nations and their overseas colonies, European-style bicycles were soon available worldwide. By the mid-20th century, bicycles had become the primary means of transportation for millions of people around the globe.

In many western countries, the use of bicycles levelled off or declined as motorized transportation became affordable and car-centred policies led to an increasingly hostile environment for bicycles. In North America, bicycle sales declined markedly after 1905, to the point where, by the 1940s, they had largely been relegated to the role of children's toys. However, in other parts of the world, such as China, India, and European countries such as Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, the traditional utility bicycle remained a mainstay of transportation; its design changed only gradually to incorporate hand-operated brakes, with internal hub gears allowing up to seven speeds. In the Netherlands, such so-called 'granny bikes' have remained popular, and are again in production.

In North America, increasing consciousness of physical fitness and environmental preservation spawned a renaissance of bicycling in the late 1960s. Bicycle sales in the US boomed, largely in the form of the racing bicycles, long used in such events as the hugely popular Tour de France. Sales were also helped by a number of technical innovations that were new to the US market, including higher performance steel alloys and gearsets with an increasing number of gears. While 10-speeds were the rage in the 1970s, 12-speed designs were introduced in the 1980s, and today most bikes feature 18 or more speeds. By the 1980s, these newer designs had driven the three-speed bicycle from the roads. In the late 1980s, the mountain bike became particularly popular, and in the 1990s something of a major fad. These task-specific designs led many American recreational cyclists to demand a more comfortable and practical product. Manufacturers responded with the hybrid bicycle, which restored many of the features long enjoyed by riders of the time-tested European utility bikes.

Technical aspects

Legal requirements

The 1968 Vienna Convention on Road Traffic considers a bicycle to be a vehicle, and a person controlling a bicycle is considered a driver. The traffic codes of many countries reflect these definitions and demand that a bicycle satisfy certain legal requirements, sometimes even including licencing, before it can be used on public roads. In many jurisdictions it is an offense to use a bicycle that is not in roadworthy condition. In some places, bicycles must have functioning front and rear lights or lamps. As some generator or dynamo-driven lamps only operate while moving, rear reflectors are frequently also mandatory. Since a moving bicycle makes very little noise, in many countries bicycles must have a warning bell for use when approaching pedestrians, equestrians and other bicyclists.

Construction and parts

Frame

Nearly all modern upright bicycles feature the diamond frame, composed of two triangles: the front triangle and the rear triangle. The front triangle consists of the head tube, top tube, down tube and seat tube. The head tube contains the headset, the set of bearings that allows the fork to spin smoothly. The top tube connects the head tube to the seat tube at the top, and the down tube connects the head tube to the bottom bracket. The rear triangle consists of the seat tube and paired chain stays and seat stays. The chain stays run parallel to the chain, connecting the bottom bracket to the rear dropouts. The seat stays connect the top of the seat tube at or near the same point as the top tube) to the rear dropouts.

Historically, women's bicycle frames had a top tube that connected in the middle of the seat tube instead of the top, resulting in a lower standover height. This allowed the rider to dismount while wearing a skirt or dress. Although some women's bicycles continue to use this frame style, there is also a hybrid form, the mixte or step-through frame, which also allows easier mounting and dismounting for both male and female riders.

Historically, materials used in bicycles have followed a similar pattern as in aircraft, the goal being strength and low weight. Since the late 1930s alloy steels have been used for frame and fork tubes in higher quality machines. Celluloid found application in mudguards, and aluminium alloys are increasingly used in components such as handlebars, seat post, and brake levers. In the 1980s aluminium alloy frames became popular, and their affordability now makes them common. More expensive carbon fiber and titanium frames are now also available, as well as advanced steel alloys.

Drivetrain

The drivetrain begins with pedals which rotate the crankset, which fit into the bottom bracket. Attached to the crank is the chainring or sprocket which drives the chain, which in turn rotates the rear wheel via the rear sprockets, or cassette. Various gearing systems, described below, may be interspersed between the pedals and rear wheel; these gearing systems vary the number of rear wheel revolutions produced by each turn of the pedals.

Since cyclists' legs produce a limited amount of power most efficiently over a narrow range of cadences, a variable gear ratio is needed to maintain an optimum pedaling speed while covering varied terrain. The gear systems are usually hand-operated, via cables (or rarely, hydraulics), and are of two types.

- Internal hub gearing works by planetary, or epicyclic, gearing, in which the outer case of the hub gear unit turns at a different speed relative to the rear axle depending on which gear is selected. Rear hub gears may offer 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, or 14 speeds. Bottom bracket fittings offer a choice of 2 speeds, and are generally foot-operated.

- External gearing utilizes derailleurs, which can be placed on both the front chainring and on the rear cluster or cassette, to push the chain to either side, derailing it from the sprockets. The sides of the gear rings catch the chain, pulling it up onto their teeth to change gears. There may be 1 to 3 chainrings, and 5 to 10 sprockets on the cassette.

Internal hub gears are much less affected by adverse weather conditions than derailleurs, and often last longer and require less maintenance. However, they may be heavier and/or more expensive, and often do not offer the same range or number of gears. Internal hub gearing still predominates in some regions, particularly on utility bikes, whereas in other regions, such as the USA, external derailleur systems predominate.

Road bicycles have close set multi-step gearing, which allows very fine control of cadence, while utility cycles offer fewer, more widely spaced speeds. Mountain bikes and most entry-level road racing bikes may offer an extremely low gear to facilitate climbing slowly on steep hills.

Fixed-gear track racing bikes have transmission efficiencies of over 99% (nearly all the energy put in at the pedals ends up at the wheel). While generally variable ratio gear mechanisms are essential for human efficiency, they do reduce mechanical efficiency. The efficiency varies considerably with the gear ratio being used. In a typical hub gear mechanism the mechanical efficiency will be between 82% and 92% depending on the ratio selected. Which ratios are best and worst depends on the specific model of hub gear. Derailleur type mechanisms fare better, with a typical mid-range product (of the sort used by serious amateurs) achieving between 88% and 99% efficiency at 100W. In derailleur mechanisms the highest efficiency is achieved by the larger cogs. Efficiency generally decreases with smaller cog sizes because the chain must bend more sharply as it rolls on and off the cog, and it also forms a sharp angle at the chain tensioner. See Chapter 9 of "Bicycling Science" (Reference, below) for details of transmission efficiency.</ref> Derailleur efficiency is also compromised with cross-chaining, or running large-ring to large-cog or small-ring to small-cog. This also results in increased wear because of the lateral deflection of the chain. Retro-Direct drivetrains used on some early 20th century bicycles have been resurrected by bicycle hobbyists.

Some early 20th C. bicycles dispensed with the chain entirely and used an enclosed driveshaft and bevel gears. These were strongly built but were not mechanically efficient. They were primarily marketed to women as the enclosed gears would not entangle clothing.

Steering and seating

The handlebars rotate the fork and the front wheel via the stem, which articulates with the headset. Three styles of handlebar are common. Touring handlebars, the norm in Europe and elsewhere until the 1970s, curve gently back toward the rider, offering a natural grip and comfortable upright position. Racing handlebars are "dropped", offering the cyclist either an aerodynamic "hunched" position or a more upright posture in which the hands grip the brake lever mounts. Mountain bikes feature a crosswise handlebar, which helps prevent the rider from pitching over the front in case of sudden deceleration.

Variations on these styles exist. Bullhorn style handlebars are often seen on modern time trial bicycles, equipped with two forward-facing extensions, allowing a rider to rest his entire forearm on the bar. These are usually used in conjunction with the aero bar, a pair of forward-facing extensions spaced close together, to promote better aerodynamics. The Bullhhorn was banned from ordinary road racing because it is difficult for the rider to control in bike traffic.

Seats, or saddles, also vary with rider preference, from the cushioned ones favoured by short-distance riders to narrower seats which allow more free leg swings. Comfort depends on riding position. With comfort bikes and hybrids the cyclist sits high over the seat, their weight directed down onto the saddle, such that a wider and more cushioned saddle is preferable. For racing bikes where the rider is bent over, weight is more evenly distributed between the handlebars and saddle, and the hips are flexed, and a narrower and harder saddle is more efficient.

Recumbent bicycles have more chair-like seats, and so are much more comfortable to ride, although generally slower up hills due to this positioning. The reclined, low seating position does provide increased aerodynamics over standard seating.

Brakes

Modern bicycle brakes are either rim brakes, in which friction pads are compressed against the wheel rims, internal hub brakes, in which the friction pads are contained within the wheel hubs, or disc brakes. A rear hub brake may be either hand-operated or pedal-actuated, as in the back pedal coaster brakes which were the rule in North America until the 1960s. Hub drum brakes do not cope well with extended braking, so rim brakes are favoured in hilly terrain. With hand-operated brakes, force is applied to brake handles mounted on the handle bars and then transmitted via Bowden cables to the friction pads. In the late 1990s, disc brakes appeared on some off-road bicycles, tandems and recumbent bicycles, but are considered impractical on road bicycles, which rarely encounter conditions where the advantages of discs are significant.

The advantages of discs make them well-suited to steep, extended downhills through wet and muddy off-road terrain, which falls under the category of downhill and freeride bicycle riding. The use of tires as large as 3.0 inches in width also makes disc brakes a necessity, as rim brakes simply cannot straddle a tire that wide.

Two main disc brake systems exist: hydraulic and mechanical (cable-actuated). Mechanical disc brakes have less modulation than hydraulic disc brake systems, and since the cable is usually open to the outside, mechanical disc brakes tend to pick up small bits of dirt and grit in the cable lines when ridden in harsh terrain. Hydraulic disc brake systems generally keep contaminants out better. However, since hydraulic disc brakes usually require relatively specialized tools to bleed the brake systems, repairs on the trail are difficult to perform, whereas mechanical disc brakes rarely fail. Also, the hydraulic fluid may boil on steep, continuous downhills. This is due to heat building up in the disc and pads and can cause the brake to lose its ability to transmit force through incompressible fluids, since some of it has become a gas, which is compressible. To avoid this problem, 203 mm (8 inch) diameter disc rotors have become common on downhill bikes. Larger rotors dissipate heat more quickly and have a larger amount of mass to absorb heat. For these reasons, one must weigh the advantages and disadvantages of using a hydraulic system versus a mechanical system.

For track cycling, track bicycles do not have brakes. Most track bike frames and forks do not have holes for mounting brakes, although with their increasing popularity among some road cyclists, some manufacturers have drilled their track frames to enable the fitting of brakes. Brakes are not required for riding on a track because all riders ride in the same direction and there are no corners or other traffic. Track rider are still able to slow down because all track bicycles are fixed, meaning that there is no freewheel. Without a freewheel, coasting is impossible, so when the rear wheel is moving, the crank is moving. To slow down one may apply resistance to the pedals. Cyclists who ride a track bike without brake(s) on the road can also slow down by skidding, by unweighting the rear wheel and applying a backwards force to the pedals, causing the rear wheel to lock up and slide along the road.

Accessories and repairs

Utility bicycles have many standard features which enhance their usefulness and comfort that would be considered accessories on sports bicycles. Chainguards and mudguards, or fenders, protect clothes and moving parts from oil and spray. Kick stands help with parking. Front-mounted wicker or steel baskets for carrying goods are often used. Rear racks or carriers can be used to carry items such as school satchels. Parents sometimes add rear-mounted child seats and/or an auxiliary saddle fitted to the crossbar to transport children.

Other accessories include lights, pump, lock, and additional (pedal or wheel-mounted) reflectors. Technical accessories include solid-state speedometers and odometers for measuring distance. Toe-clips and toestraps help to keep the foot planted firmly on the pedals, and enable the cyclist to pull as well as push the pedals.

In most countries where cycling is common, bicycle helmet use is negligible. In North America a significant minority, possibly up to 25% of bicyclists, wear helmets. While no U.S. federal law requires helmets, many states require children to wear them, and some municipalities require them for all riders. In Australia and New Zealand, and parts of Canada, helmets are required by law. Outside the West, use of helmets by utility cyclists is practically unknown. No correlation between decreased injury rates and helmet use has been demonstrated in whole populations.

Many cyclists carry tool kits, containing at least a tire patch kit (and/or a spare tube), tire levers, and allen wrenches. A single tool once sufficed for most repairs. More specialised parts now require more complex tools, including proprietary tools specific for a given manufacturer. Some bicycle parts, particularly hub-based gearing systems, are complex, and many prefer to leave maintenance and repairs to professionals. Others maintain their own bicycles, enhancing their enjoyment of the hobby of cycling.

Performance

In both biological and mechanical terms, the bicycle is extraordinarily efficient. In terms of the amount of energy a person must expend to travel a given distance, investigators have calculated it to be the most efficient self-powered means of transportation. From a mechanical viewpoint, up to 99% of the energy delivered by the rider into the pedals is transmitted to the wheels, although the use of gearing mechanisms may reduce this by 10-15%. In terms of the ratio of cargo weight a bicycle can carry to total weight, it is also a most efficient means of cargo transportation.

A human being travelling on a bicycle at low to medium speeds of around 10-15 mph (16-24 km/h), using only the energy required to walk, is the most energy-efficient means of transport generally available. Air drag, which increases with the square of speed, requires increasingly higher power outputs relative to speed. A bicycle in which the rider lies in a prone position and which may be covered in an aerodynamic fairing to achieve very low air drag is referred to as a Recumbent bicycle or Human Powered Vehicle.

For more detail, see bicycle performance

Balance

A bicycle stays upright when it is steered to keep its center of gravity over its wheels. Lock the steering of a bicycle and it is virtually impossible to ride. Cancel the gyroscopic effect of rotating bicycle wheels by adding counter-rotating wheels, and it can still be easily ridden.

Further reading

For more information on the technical aspects of bicycles, see also:

Social and historical aspects

Economic implications

Bicycle manufacturing proved to be a training ground for other industries. Building modern bicycle frames led to the development of advanced metalworking techniques, both for the frames themselves and for special components such as ball bearings, washers, and sprockets. These techniques later enabled skilled metalworkers and mechanics to develop the components used in early automobiles and aircraft. J. K. Starley's company became the Rover Cycle Company Ltd. in the late 1890s, and then the Rover auto maker. The Morris Motor Company (in Oxford) and Škoda also began in the bicycle business, as did Henry Ford and the Wright Brothers.

Some bicycle clubs and national associations became prominent advocates for improvements to roads and highways. In the United States, the League of American Wheelmen lobbied for the improvement of roads in the last part of the 19th century, founding and leading the national Good Roads Movement. Both their model for political organization and the paved roads for which they argued facilitated the growth of the bicycle's rival, the automobile.

In recent years, US and European bicycle makers have moved much of their production to Asia. Some sixty percent of the world's bicycles are now being made in China. Despite this shift in production, as nations such as China and India become more wealthy, their own use of bicycles has declined. One of the major reasons for the proliferation of Chinese-made bicycles in foreign markets is the increasing affordability of cars and motorcycles for its own citizens.

Female emancipation

The diamond-frame safety bicycle gave women unprecedented mobility, contributing to their emancipation in Western nations. As bicycles became safer and cheaper, more women had access to the personal freedom they embodied, and so the bicycle came to symbolise the New Woman of the late nineteenth century, especially in Britain and the United States.

The bicycle was recognised by nineteenth-century feminists and suffragists as a "freedom machine" for women. American Susan B. Anthony said: "Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel...the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood." In 1895 Frances Willard, the tightly-laced president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, wrote a book called How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, in which she praised the bicycle she learned to ride late in life, and which she named "Gladys", for its "gladdening effect" on her health and political optimism. Willard used a cycling metaphor to urge other suffragists to action, proclaiming, "I would not waste my life in friction when it could be turned into momentum."

The male anger at the freedom symbolised by the New (bicycling) Woman was demonstrated when the male undergraduates of Cambridge University chose to show their opposition to the admission of women as full members of the university by hanging a woman in effigy in the main town square -- tellingly, a woman on a bicycle. This was as late as 1897.[1]

In the 1890s the bicycle craze led to a movement for so-called rational dress, which helped liberate women from corsets and ankle-length skirts and other restrictive garments, substituting the then-shocking bloomers.

Other social implications

Sociologists suggest that bicycles enlarged the gene pool for rural workers, by enabling them to easily reach the next town and increase their courting radius. In cities, bicycles helped reduce crowding in inner-city tenements by allowing workers to commute from more spacious dwellings in the suburbs. They also reduced dependence on horses, with all the knock-on effects this brought to society. Bicycles allowed people to travel for leisure into the country, since bicycles were three times as energy efficient as walking, and three to four times as fast.

Uses for bicycles

Bicycles at work

The postal services of many countries have long relied on bicycles. The British Royal Mail first started using bicycles in 1880; now bicycle delivery fleets include 37,000 in the UK, 25,700 in Germany and 10,500 in Hungary. The London Ambulance Service has recently introduced bicycling paramedics, who can often get to the scene of an incident in Central London more quickly than a motorised ambulance.

Police officers adopted the bicycle as well, initially using their own. However, they eventually became a standard issue, particularly for police in rural areas. The Kent police purchased 20 bicycles in 1896, and by 1904 there were 129 police bicycle patrols operating. Some countries retained the police bicycle while others dispensed with them for a time. Bicycle patrols are now enjoying a resurgence in many cities, as the mobility of car-borne officers is becoming increasingly limited by traffic congestion and pedestrianisation. They also have the advantages that the officers are inherently more open to the public, and the transport is quieter to permit a more stealthy approach toward suspects. The pursuit of suspects can also be assisted by a bicycle.

Bicycles enjoy substantial use as general delivery vehicles in many countries. In the UK and North America, generations of teenagers have got their first jobs delivering newspapers by bicycle. London has many delivery companies that use bicycles with trailers. Most cities in the West, and many outside it, support a sizable and visible industry of cycle couriers who deliver documents and small packages. In India, many of Mumbai's Dabbawalas use bicycles to deliver hot lunches to the city’s workers. In Bogotá, Colombia the city’s largest bakery recently replaced most of its delivery trucks with bicycles. Even the car industry uses bicycles. At the huge Mercedes-Benz factory in Sindelfingen, Germany workers use bicycles, colour-coded by department, to move around the factory.

Bicycle recreation

Bicycles are used for recreation at all ages. Bicycle touring, also known as cyclotourism, involves touring and exploration or sightseeing by bicycle for leisure. A brevet or randonnée is an organized long-distance ride.

One aspect of Dutch popular culture is enjoying relaxed cycling in the countryside of the Netherlands. The land is very flat and full of public bicycle trails where cyclist aren't bothered by cars and other traffic, which makes it ideal for cycling recreation. Many Dutch people subscribe every year to an event called fietsvierdaagse — four days of organised cycling through the local environment. Paris-Brest-Paris (PBP), which began in 1891, is the oldest bicycling event still run on a regular basis on the open road, covers over 1200 km and imposes a 90-hour time limit.

Bicycles and war

The bicycle is not suited for combat, but it has been used as a method of transporting soldiers and supplies to combat zones. Bicycles were used in the Second Boer War, where both sides used them for scouting. In World War I, France and Germany used bicycles to move troops. In its 1937 invasion of China, Japan employed some 50,000 bicycle troops, and similar forces were instrumental in Japan's march through Malaya in World War II. Germany used bicycles again in World War II, while the British employed airborne Cycle-commandos with folding bikes.

In the Vietnam War, communist forces used bicycles extensively as cargo carriers along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. There are reports of mountain bicycles being used in scouting by U.S. Special Forces in the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and in subsequent battles against the Taliban. The only country to recently maintain a regiment of bicycle troops was Switzerland, who disbanded the last unit in 2003.

Bicycle racing

Shortly after the introduction of bicycles, competitions developed independently in many parts of the world. Early races involving boneshaker style bicycles were predictably fraught with injuries. Large races became popular during the 1890's "Golden Age of Cycling", with events across Europe, and in the U.S. and Japan as well. At one point, almost every major city in the US had a velodrome or two for track racing events. However since the middle of the 20th Century cycling has become a minority sport in the US whilst in Continental Europe it continues to be a major sport, particularly in France, Belgium and Italy. The most famous of all bicycle races is the Tour de France. This began in 1903, and continues to capture the attention of the sporting world.

As the bicycle evolved its various forms, different racing formats developed. Road races may involve both team and individual competition, and are contested in various ways. They range from the one-day road race, criterium, and time trial to multi-stage events like the Tour de France and its sister events which make up cycling's Grand Tours. Recumbent bicycles were banned from bike races in 1934 after Marcel Berthet set a new hour record in his Velodyne streamliner (49.992 km on Nov 18, 1933). Track bicycles are used for track racing in Velodromes , while cyclo-cross races are held on rugged outdoor terrain. In the past decade, mountain bike racing has also reached international popularity and is even an Olympic sport.

The governing body of international cycle sport, the Union Cycliste Internationale, decided in the late 1990s to create additional rules restricting the design of racing bicycles. These rules met with considerable controversy and to some extent arrested the development of the racing bicycle. Their stated motive was so that developing countries could compete in international competitions without requiring large equipment budgets, and to re-focus attention on the athlete rather than the bicyle. For example, monocoque frames, such as used by Chris Boardman to win the Gold medal in 1992 Olympic individual pursuit event in Barcelona, were no longer permitted.

Cyclists and motorists make different demands on road design which may lead to conflicts both in politics and on the streets. Some jurisdictions give priority to motorised traffic, for example setting up extensive one-way street systems, free-right turns, high capacity roundabouts, and slip roads. Other cities may apply active traffic restraint measures to limit the impact of motorised transport. In the former cases, cycling has tended to decline while in the latter it has tended to be maintained. Occasionally, extreme measures against cycling may occur. In Shanghai, a city where bicycles were once the dominant mode of transportation, bicycle travel on city roads was actually banned temporarily in December 2003.

In areas in which cycling is popular and encouraged, cycle-parking facilities using bicycle racks, lockable mini-garages, and patrolled cycle parks are used to reduce theft. Local governments also promote cycling by permitting the carriage of bicycles on public transport or by providing external attachment devices on public transport vehicles. Conversely, an absence of secure cycle-parking is a recurring complaint by cyclists from cities with low modal share of cycling.

Extensive bicycle path systems may be found in some cities. Such dedicated paths often have to be shared with inline skaters, scooters, skateboarders, and pedestrians. Segregating bicycle and automobile traffic in cities has met with mixed success, both in terms of safety and bicycle promotion. At some point the two streams of traffic inevitably intersect, often in a haphazard and congested fashion. Studies have demonstrated that, due to the high incidence of accidents at these sites, such segregated schemes can actually increase the number of car-bike collisions.

Cycling activism

Cyclists form associations, both for specific interests (trails development, road maintenance, urban design, racing clubs, touring clubs, etc.) and for more global goals (energy conservation, pollution reduction, promotion of fitness). Two broad themes run in bicycle activism: one more overtly political with roots in the environmental movement; the other drawing on the traditions of the established bicycle lobby.

Such groups promote the bicycle as an alternative mode of transport and emphasize the potential for energy and resource conservation and health benefits gained from cycling versus automobile use. Activists in both camps also argue for improved local and inter-city rail services and other methods of mass transportation, and also for greater provision for cycle carriage on such services. Many cities also have community bicycle programs that promote cycling, especially as a means of inner-city transport.

Controversially, some bicycle activists (including some traffic management advisors) seek the construction of segregated cycle facilities for journeys of all lengths. Other activists, especially those from the more established tradition, view the safety, practicality, and intent of many segregated cycle facilities with suspicion. They favour a more holistic approach based on the 4 'E's; education (of everyone involved), encouragement (to apply the education), enforcement (to protect the rights of others), and engineering (to facilitate travel while respecting every person's equal right to do so). In some cases this opposition has a more ideological basis: some members of the Vehicular Cycling movement oppose segregated public facilities, such as on-street bike lanes, on principle. Some groups offer training courses to help cyclists integrate themselves with other traffic. This is part of the ongoing cycle path debate.

Critical Mass is a worldwide activist movement of mass bicycle protest rides. It incorporates the themes of increasing the road- and mind-share given to bicycle transport, and has drawn support from environmentally minded campaigners and other schools of political thought. According to participants in Critical Mass, "We aren't blocking traffic, we are traffic!" However, their particular forms of protest has drawn criticism from the broader streams of activism.

There is a long-running cycle helmet debate among activists. The most heated controversy surrounds the topic of compulsory helmet use.

Types of bicycle

There are many different types of bicycle. See also Category:Cycle types.

By function

- Utility bicycles are designed for commuting, shopping and running errands. They employ middle or heavy weight frames and tires, internal hub gearing, and a variety of helpful accessories. The riding position is usually upright.

- Mountain bicycles are designed for off-road cycling, and include other sub-types of off-road bicycles such as Cross Country (i.e."XC"), Downhill , and to a lesser extent Freeride bicycles. All mountain bicycles feature sturdy, highly durable frames and wheels, wide-gauge treaded tires, and cross-wise handlebars to help the rider resist sudden jolts. Some mountain bicycles feature various types of suspension systems (e.g. coiled spring, air or gas shock), and hydraulic or mechanical disc brakes. Mountain bicycle gearing is very wide-ranging, from very low ratios to high ratios, typicaly with 21 to 30 gears.

- Racing bicycles are designed for speed, and include road, time trial, and track bicycles. They have lightweight frames and components with minimal accessories, dropped handlebars to allow for an aerodynamic riding position, narrow high-pressure tires for minimal rolling resistance and multiple gears. Racing bicycles have a relatively narrow gear range, and typically varies from medium to very high ratios, distributed across 18, 20, 27 or 30 gears. The more closely spaced gear ratios allow racers to choose a gear which will enable them to ride at their optimun pedaling cadence for maximum efficency.

- Time trial bicycles are similar to road bicycles but are differentiated by a more aggressive frame geometry that throws the rider into a more compact (i.e "aero") riding position. They also feature aerodynamic frames, wheels, and handlebars.

- Track bicycles, intended for indoor or outdoor cycle tracks or velodromes, are exceptionally simple compared with road bikes. They have a single gear ratio, a fixed drivetrain (i.e. no freewheel), no brakes, and are minimally adorned with other components that would otherwise be typical for a racing bicycle.

- Messenger bikes are typically used for urgent deliveries of letters and small packages between businesses in big cities with heavily congested traffic. While any bike can be used, messenger bikes often resemble track bicycles (especially in the USA).

- Touring bicycles are designed for bicycle touring and long journeys. They are durable and comfortable, capable of transporting baggage, and may feature any type of gearing system.

- Randonneur or Audax bicycles are designed for randonnées or brevet rides, and fall in between racing bicycles and those intended for touring.

- Recumbent bicycles, which are sometimes referred to as Bents in the USA, are designed to maximise comfort and minimise wind resistance. Whereas most of the other types of bicycle in this section are designed around a ‘diamond frame’ geometary, where the pedals and chainset are located at the bottom of the bicycle and handlebars are at the front, recumbent bicycles (recumbents) generally use a “boom” and rear triangle combination with the pedals and chainset located at the front of the boom and the handlebars are located either “over seat” or “underseat” in the centre.

By number of riders

- A tandem or twin has two riders.

- A triplet has three riders; a quadruplet has four.

- The largest multi-bike had 40 riders.[2]

In most of these types the riders ride one behind the other. Exceptions are "The Companion", or "sociable," a side-by-side two-person bike (that converted to a single-rider) built by the Punnett Cycle Mfg. Co. in Rochester, N. Y. in the 1890s. Another bicycle, the "Conference Bike", rented to tourists in Berlin carries seven people seated in a circle.

By general construction

- A penny-farthing or ordinary has one high wheel directly driven by the pedals and one small wheel.

- On an upright bicycle the rider sits astride the saddle. This is the most common type.

- On a recumbent bicycle the rider reclines or lies supine.

- A Pedersen bicycle has a bridge truss frame.

- A folding bicycle can be quickly folded for easy carrying, for example on public transport.

- A Moulton Bicycle has a traditional seating position, and utilises small diameter, high pressure tires and front and rear suspension.

- An exercise bicycle remains stationary; it is used for exercise rather than propulsion.

By gearing

- Internal hub gearing is most common in European utility bicycles, usually ranging from three-speed bicycles to five and seven speed options. But hub gears with eight and fourteen speeds are available as well.

- Shaft-driven bicycles use a driveshaft rather than a chain to power the rear wheel. These are often used as commuter bikes because they eliminate inconveniences associated with chains and pant-legs, but they are less efficient than chain-driven bicycles. Shaft- driven bicycles usually employ internal hub gearing.

- Derailleur gears, featured on most racing and touring bicycles, offering from 5 to 30 speeds

- Single-speed bicycles and Fixed-gear bicycles have only one gear, and include all BMX bikes, children's bikes, crowded city messenger bikes, and many others. The fixed gear has no freewheel mechanism, so whenever the bike is in motion the pedals continue to spin. An advantage of this is the pedals can also be used to slow down.

- Retro-Direct bicycles have two sprockets on the rear wheel. By backpedaling, the secondary, usually lower, gear is engaged.

By sport

- Track bicycles are ultra-simple, lightweight fixed-gear bikes with no brakes, designed for track cycling on purpose-built cycle tracks, often in velodromes.

- Time trial bicycles are similar to road bicycles with an extremely aerodynamic design for use in a cycling time trial.

- Cyclo-cross bicycles are lightweight enough to be carried over obstacles, and robust enough to be cycled through mud.

- Down-hill racers are a specialized type of mountain bike with a very strong frame, altered geometry, and long travel suspension. They are designed for use only on downhill tracks.

- BMX (bicycle motocross) bicycles have small wheels and are used for BMX racing, as well as freestyle with tricks such as wheelies. Freestyle BMXers often ride dirt jumps and skatepark ramps.

- Triathlon bicycles have seat posts that are closer to vertical than the seat posts on road racing bicycles. This concentrates the effort of cycling in the quadriceps muscles, sparing the other large muscles of the leg for the running segment of the race. Triathlon bicycles also have specialized handlebars known as triathlon bars or aero bars.

By means of propulsion

- A pedal cycle is driven by pedals.

- A hand-cranked bicycle is driven by a hand crank.

- A rowing bicycle is driven by a rowing action using both arms and legs.

- A Motorized bicycle provides motor assistance.

- A moped propels the rider with a motor, but includes bicycle pedals for human propulsion.

- a "Flywheel" uses stored kinetic energy.

Other types

- Hybrid bicycles are a compromise between the mountain and racing style bicycles which replaced European-style utility bikes in North America in the early 1990s. They have a light frame, medium gauge wheels, and derailleur gearing, and feature straight or curved-back, touring handlebars for more upright riding.

- Cruiser bicycles are designed for comfort, with curved back handlebars, padded seats, and balloon tires. Cruisers typically have minimal gearing and are often available for rental at beaches and parks which feature flat terrain.

- Freight bicycles are designed for transporting large or heavy loads.

- Cycle rickshaws (also called pedicabs or trishaws) are used to transport passengers for hire.

- Velomobiles or bicycle cars provide enclosed pedal-powered transportation.

- Clown bicycles are designed for comedic effect or stunt riding. Some types of clown bicycles are:

- bucking bike (with one or more eccentric wheels)

- tall bike (often called an upside down bike, constructed so that the pedals, seat and handlebars are all higher than normal) -- other types of tall bikes are made by welding two or more bicycle frames on top of each other, and running additional chains from the pedals to the rear wheel.

- Come-apart bike, (essentially a unicycle, plus a set of handlebars attached to forks and a wheel).

- Clown bikes are also built that are directly geared, with no freewheeling, so that they may be pedaled backwards. Some are built very small but are otherwise normal.

- Art bikes: Some bikes are built so that the frame appears to be made of junk or found objects: Bongo the Clown built several ridable parade bikes which were as much kinetic sculptures as transport.

- A unicycle is not a bicycle, as it has only one wheel, but it is related.

Standards

A number of formal and industry standards exist for bicycle components, to help make spare parts exchangeable:

- ISO 5775 Bicycle tire and rim designations

- ISO 8090 Cycles — Terminology (same as BS 6102-4)

- ISO 4210 Cycles — Safety requirements for bicycles

See also

- Bicycle gearing

- Bicycle lift

- Bicycle lighting

- Bicycle lock

- Bicycle messenger

- Bicycle performance

- Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics

- Bicycle safety

- Bicycling terminology

- Bicycle trailer

- Clothing-optional bike rides

- Clown bicycle

- Countersteering

- Cycle rickshaw

- Cycling

- Cycling hand signals

- Fietsvierdaagse

- French bicycle industry

- List of bicycle manufacturers

- List of environment topics

- List of important cycling events

- Motorcycles

- Mountain biking

- Quadricycle

- Racing bicycle

- Raleigh Chopper

- Recumbent bicycle

- Segregated cycle facilities

- Safety standards

- Tandem bicycle

- Timeline of transportation technology

- Tricycle

- Utility cycling

- Vehicular cycling

References

- All About Bicycling, Rand McNally.

- Richard Ballantine, Richard's Bicycle Book, Pan, 1975.

- Caunter C. F. The History and Development of Cycles Science Museum London 1972.

- Daniel Kirshner. Some nonexplanations of bicycle stability. American Journal of Physics, 48(1), 1980. The abstract reads "In this paper we attempt to verify a nongyroscopic theory of bicycle stability, and fail".

- David B. Perry, Bike Cult: the Ultimate Guide to Human-powered Vehicles, Four Walls Eight Windows, 1995.

- Roni Sarig, The Everything Bicycle Book, Adams Media Corporation, 1997

- US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. "America's Highways 1776-1976", pp. 42-43. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office.

- David Gordon Wilson, Bicycling Science, MIT press, ISBN 0-262-73154-1

- David V. Herlihy, Bicycle: The History, Yale University Press, 2004

- Frank Berto, The Dancing Chain: History and Development of the Derailleur Bicycle, San Francisco: Van der Plas Publications, 2005, ISBN 1-892495-41-4.

- The Data Book: 100 Years of Bicycle Component and Accessory Design, San Francisco: Van der Plas Publications, 2005, ISBN 1-892495-01-5.

External links

- The World's Bicycle Conference: Velo Mondial

- Brown, Sheldon (2005). Extensive online bicycle glossary.

- eHow, Inc. (2005). How to Make Your Bike the Perfect Fit. Retrieved March 30, 2005.

- European Cyclists' Federation

- Exploratorium (2004). Science of Cycling: Human Power. Retrieved March 30, 2005.

- Hudson, William (2003). Myths and Milestones in Bicycle Evolution. Retrieved March 30, 2005.

- Jones, David E. H. (1970). The Stability of the Bicycle. Scanned in copy for download for personal use.